WASHINGTON -- The Eagle, Globe, and Anchor is the official emblem of the United States Marine Corps. However, its roots can be traced all the way back to as far as 1804, with uniforms of Marines being adorned with brass eagles on square plates. During the War of 1812, this early emblem morphed into an octagonal brass plate embossed with an eagle, an anchor, drums, and flags. As the decades would progress, symbols on the emblem would be replaced with letters. Starting in 1840, Marine uniforms would see the metal letters “U.S.M.” During the subsequent years, more changes, modifications, and additions ensued until in 1868, when Marine leaders believed their insignia too closely resembled that of the U.S. Army infantry, and began to take steps to make a distinctive device. Commandant Brig. Gen. Jacob Zeilin appointed a special board to create a device for the Corps.

Introduced in November of 1868, almost a century after the Corps’ founding, the insignia has repeatedly evolved in design aesthetic and the material it is made out of, but what it represents has remained the same.

The eagle, perched atop the globe, symbolizes the nation the Marine Corps serves and protects, highlighting our commitment to defend the United States and her values. The globe, depicting the western hemisphere, represents the worldwide presence of the Marine Corps, echoing our expeditionary nature and readiness to protect American interests in any clime or place. The fouled anchor (an anchor wrapped in rope) shows the Corps’ naval history and our role as an amphibious force in readiness, prepared to fight in concert alongside America’s Navy, no matter the challenges faced. The Eagle, Globe, and Anchor is recognizable worldwide, reminding allies and foes that the Marine Corps remains “Always Faithful.”

Since its introduction in the 19th century, the EGAs worn on Marine uniforms have differed between officers and enlisted personnel.

The first officer EGAs were made to elaborate standards: "A frosted silver hemisphere… North and South America of gold plate… surmounted by a spread eagle cut from solid silver and securely fastened by means of a tang of silver soldered on the inner side of the hemisphere."

By contrast, the enlisted insignia was made to less ornate specifications: "same as for officers except that the whole be struck from plate brass.

According to Owen Conner, the Uniforms and Heraldry Curator at the National Museum of the Marine Corps, these differences originated from the varying prestige of each role. Officer ornaments were less standardized for much of their first century.

"Up until World War II, you see a lot more variation in styles of officer ornaments," Conner said. "They would go to jewelry places like Bailey, Banks, and Biddle... and certain companies and certain jewelers had different molds."

Variations over the years saw the position on top of the eagle shift over time – sitting, squatting, or standing. The depth of the globe itself also shifted from the presence of the longitude/latitude lines on the globe. Different manufacturers, especially in the early years, meant a wide variation in the design of the iconic emblem.

After the war, officer EGAs became more standardized and less unique.

Along with the difference in materials and variety of designs, officer and enlisted EGAs can be distinguished visually by the detail in the rope wrapping the anchor and the omission of Cuba on the officer ornament.

The officer design is more ornate, allowing for better clarity on the rope compared to the one-piece, stamped enlisted version. The intricate construction of the officer piece means that Cuba is not included in the design due to durability issues.

Enlisted Marines who feel slighted by their less ornate models sometimes find humor in their own explanation for the absence of Cuba, joking that officers simply can't find it on a map.

Because of the variation in production before World War II, it's more difficult to track the official evolution of the EGA than, say, the Marine Corps' service rifle. However, stylistic shifts can be identified and used to date ornaments. For example, Conner affectionately likened the eagle on World War I era ornaments to a "fat turkey."

The Interwar Era of the 1920s and 1930s introduced the "Droop Wing" eagle, which was a more stylized design. This version was based on drawings by a Marine artist who observed eagles at the National Zoo in Washington, D.C.

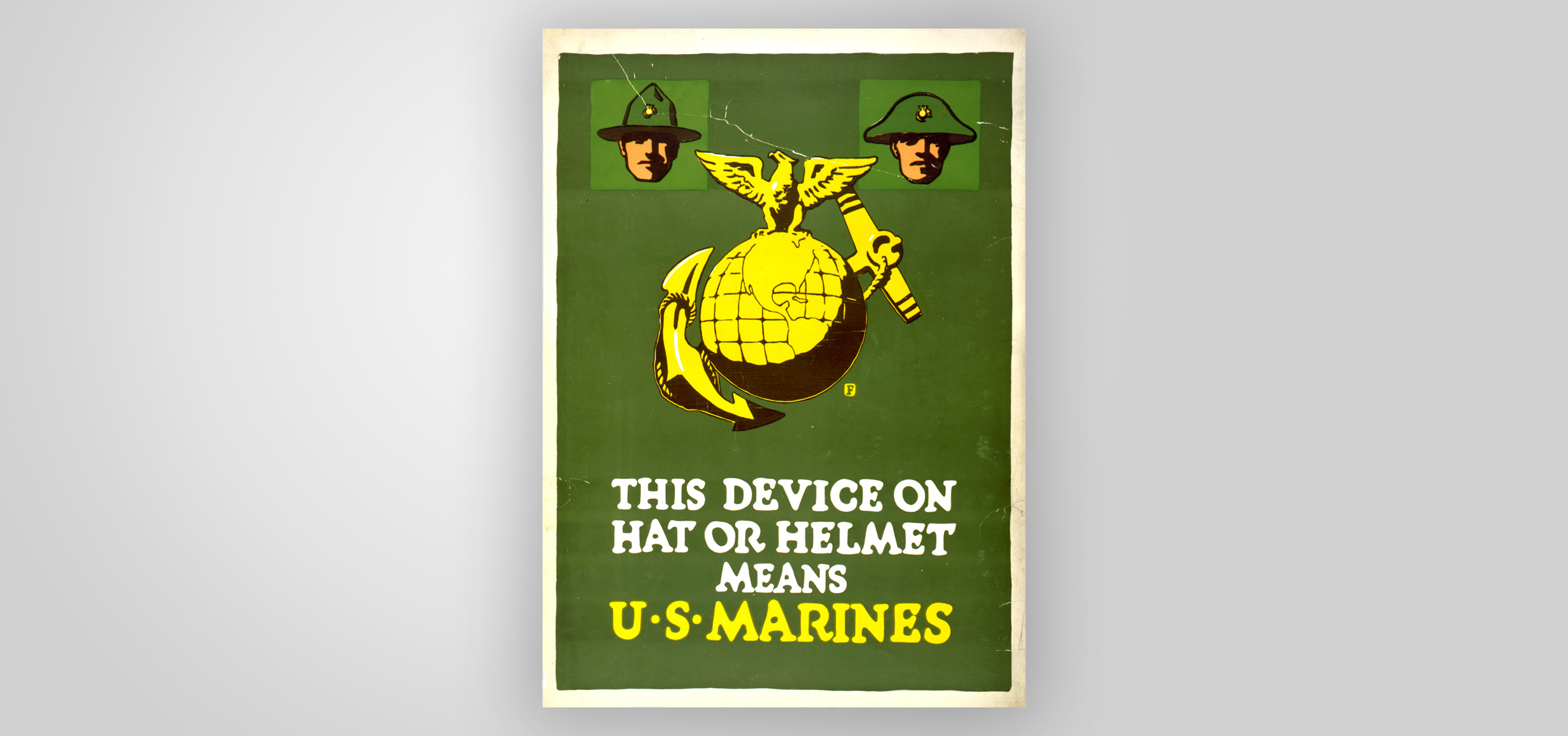

With the adoption of an official emblem, pride in the Corps grew as the decades wore on, as can be seen in this World War I recruiting poster.

The Second World War saw a lot of stylistic variation, but also the beginning of standardization. Due to wartime economy, some EGAs were made of plastic, or "bakelite," to conserve brass.

The Second World War saw a lot of stylistic variation, but also the beginning of standardization. Due to wartime economy, some EGAs were made of plastic, or "bakelite," to conserve brass.

Whether it was a hand-crafted ornament from a pre-war jeweler or a mass-produced plastic emblem from a wartime economy, the EGA has always served as a timeless and unifying symbol. Its history, full of stylistic evolutions and hidden meanings, mirrors the Marine Corps' evolution. The physical ornaments may change, but the values they represent remain steadfast, connecting every Marine, from past to present, to the same core identity, that of someone who has earned the title United States Marine.